Interfaces – A Poorly Understood Limitation to the Adoption of Digital Pathology

David C. Wilbur, M.D.

Authored by:

David C. Wilbur, M.D.

Chief Scientist, Corista LLC

Professor of Pathology Emeritus

Harvard Medical School

The microscope has been around for hundreds of years and has reached a plateau of efficiency. Certainly, in my own practice over the last 40 years, the physical process of microscopy has not changed. I still use today the microscope I bought as a resident. Sure, some advances have been made, like tilting heads and automatic turret changes, but these are designed to prevent chronic issues, such as neck and back pain and carpal tunnel syndrome, respectively. They have little to do with the daily efficiency of the process.

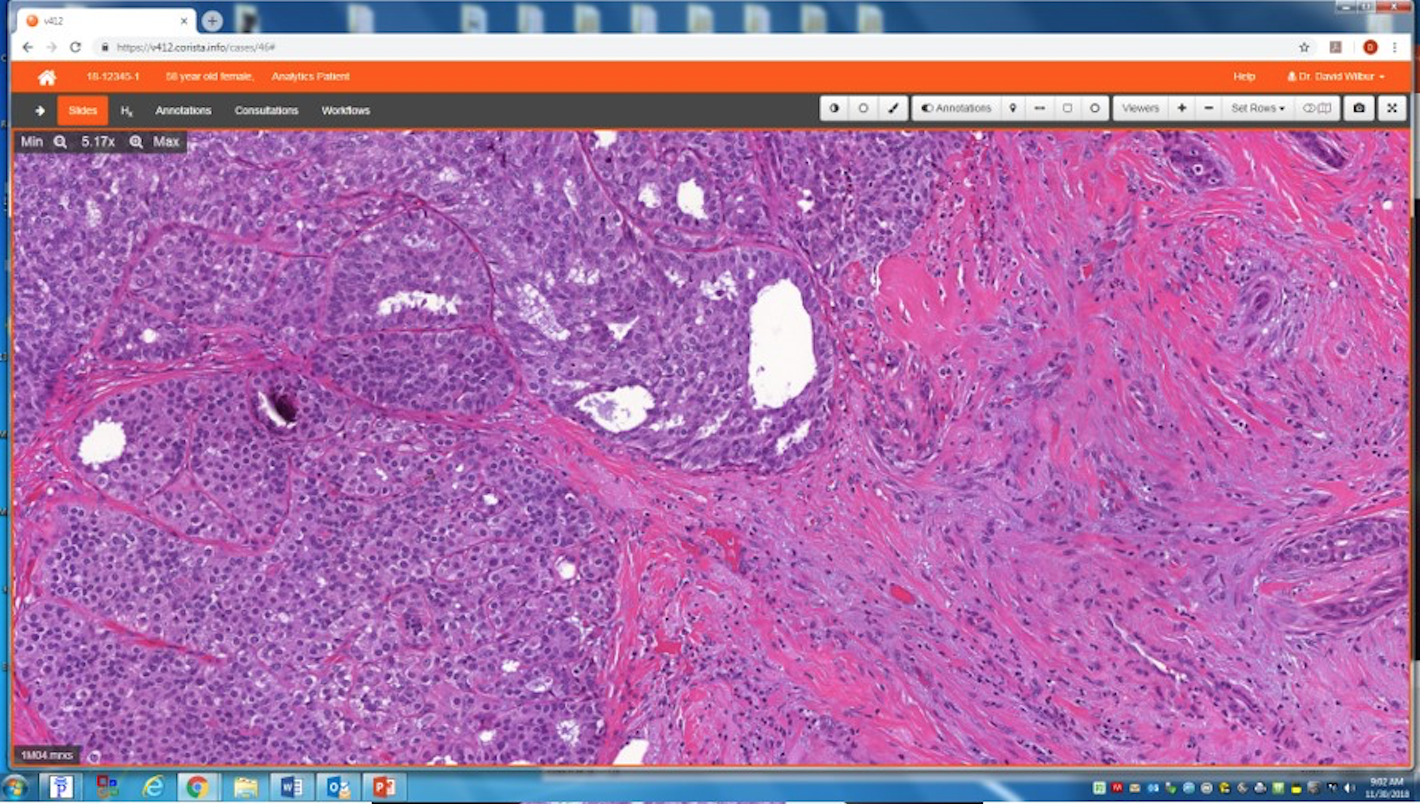

Now, along comes digital pathology and with it the interface which pathologists use to do their daily “microscopy” changes quite dramatically. A computer monitor displays a much larger field of view which is controlled by (most commonly) a hand-operated device used to navigate the image and change magnifications. Anyone who has used such a system will probably tell you that, despite manufacturers’ claims to the contrary, the process is slower and more tiring than is the use of a standard microscope to review the same histologic material. Anecdotally, I have discussed this issue with digital pathology clinical trial participants whose response to the question “would you switch,” was a definitive “no way!” despite diagnostic equivalency between the digital and standard microscopy (and FDA product approval). The reasons being exactly the issue of negativity toward the interfaces. This was further substantiated by a recent large study from Memorial Sloan Kettering in which experienced users found that a daily sign out using digital pathology review took the average pathologist over 1 hour longer than did standard microscopy practice. (1) “Average” of course means that some pathologists added even greater hours to their day’s work! General comments from that study concluded that, overall, users felt “uncomfortable” reading digital slides.

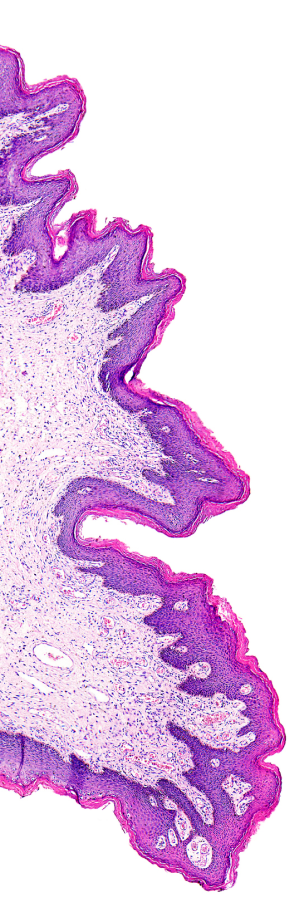

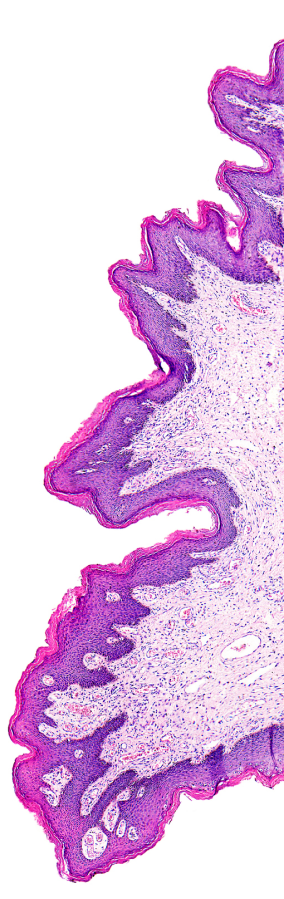

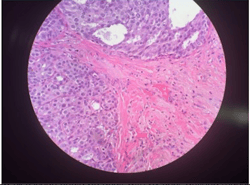

So, what are the problems – specifically; and what might be the solutions? First of all, standard microscopy navigation – either freehand or manual stage-based – uses very small and precise finger movements, which require very little physical effort. Digital navigation, using a mouse or other tool (trackball, touch screen, etc) requires very repetitive gross (large) movements which rapidly tire out the user’s arm. Secondly, the digital display field of view is much larger than what a viewer sees through a standard microscope ocular (see figure 1).

Figure 1

Legend: Comparison of the field of view (digital – upper, analog microscopy – lower) at the same magnification. A typical digital slide field of view presents far more information at the same magnification.

A digital slide presents far more material to be reviewed in a field than would be the case with a microscope at the same magnification. As a user, my (and others’) perception is that with digital slides the magnification, or image resolution, is less than through the microscope. The user has the constant impulse to increase the magnification – often beyond the capture resolution. User focus is the issue here. Interestingly studies done years ago in cytology show that even with a microscope, the user only focuses intently on the middle third of the field of view. Translate this to a 4-fold increase in field size and the problem of “user attention” becomes obvious.

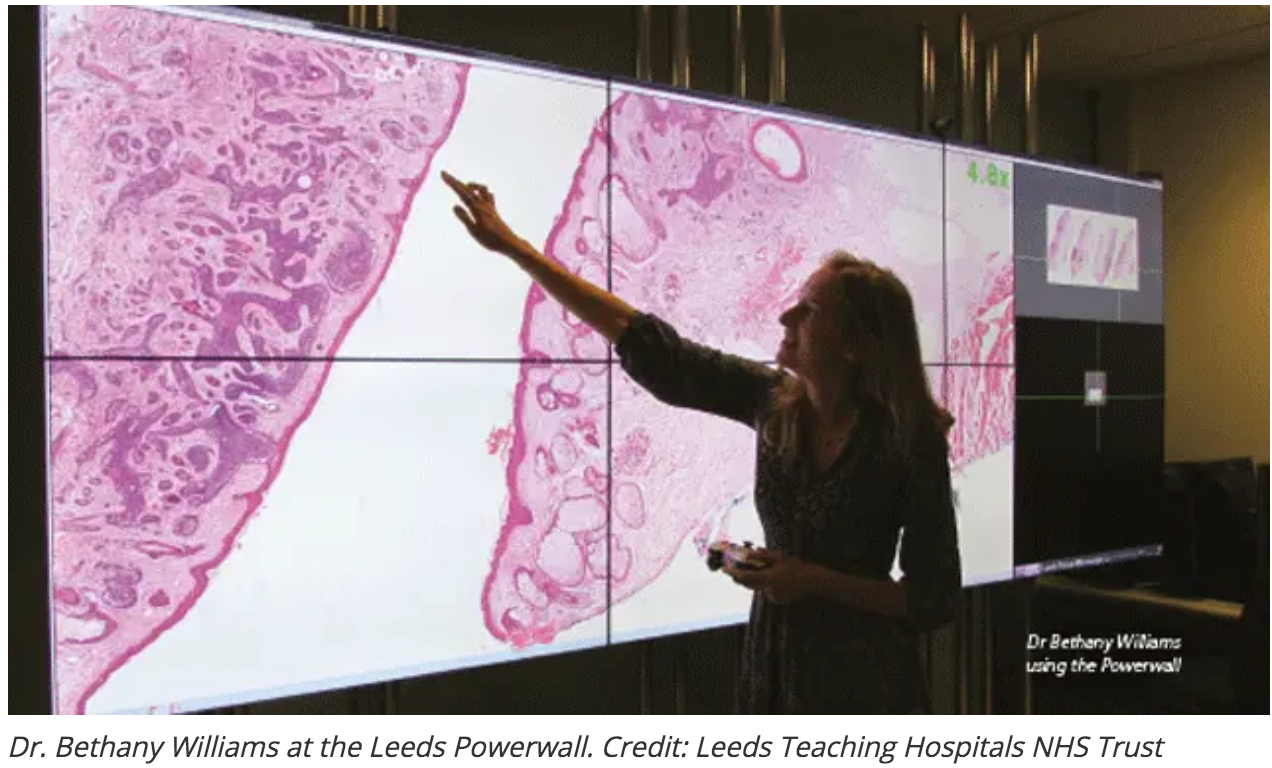

Potential solutions include use of new interface devices that alleviate the physical limitations as described above. These might include very large screens (“Powerwall” from the Leeds group (2)) that allow full resolution images to be statically displayed. The user merely moves themselves to navigate and change magnification. Other options include virtual reality headsets that allow scanning of the slide by turns of the head. Yet another option is a highly sensitive touchscreen that simulates exactly the freehand movements of a slide on a microscope stage. Two-handed control using one hand to navigate and the other to change magnifications with a second push button control could closely simulate current analog microscopy. The field of view size issue could be dealt with by user-defined masks in viewing stations that more closely recapitulate the view in the microscope. However, this problem is more likely to be a matter of user adaptation that requires more extensive experience. It is a problem that should go away when the current generation of microscopy-trained pathologists gives way to the new generation of “digital savvy” users.

In summary, the field has work to do. There is no question that digital pathology is as accurate as its age-old counterpart. (3) Ergonomic research and engineering developments will ultimately prevail, but they need to be worked on now in order to promote ongoing pathologist acceptance. In the future the digital experience will only improve as algorithms for prescreening and automated assessments come into practice. The digital environment is very well-suited to these enhancements as manipulation of the image for improved efficiency of viewing (guided screening) and interpretation (automated analytics) will be the next steps forward. Devotion to the pathologist experience within digital pathology is a must if we are to move as rapidly as possible.

References

- Hanna MG, Reuter VE, Hameed MR, et al. Whole slide imaging equivalency and efficiency study: experience at a large academic center. Mod Pathol. 2019;32:916-28.

- Treanor D, Jordan-Owers N, Hodrien J, et al. Virtual reality Powerwall versus conventional microscope for viewing pathology slides: an experimental comparison. 2009;55:294-300.

- Mills AM, Gradecki SE, Horton BJ, et al. Diagnostic efficiency in digital pathology. A comparison of optical vs. digital assessment in 510 surgical pathology cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2018;42:53-9.