The Big Miss

Keith Kaplan, MD, Chief Medical Officer

Several years ago Tiger Wood’s former golf coach wrote a book with the above title. Among providing glimpses of Tiger’s personal life, his work ethic, practice routines, diet, interaction with his wife, etc… the author of course talks about Tiger’s presence on the golf course, his swing mechanics and level of focus on the course.

Many golf books, whether they are instructional or biographical about the game’s best players, have a very common theme: golf is a game of controlled misses. Turn on the TV nearly any weekend and the golf commentators would have you believe that the players form their shots to try to record the lowest scores. They talk about their distance off the tee, spin control or putting speed. As much as they try to hit the best shot, and every shot is a new shot, and the last shot is in the past, and all the other sports psychology euphemisms, golf isn’t as much about hitting good shots in a string of holes or days of a tournament as much as it is about not hitting too many bad shots. Make the shots you should. Avoid the misses. Especially the big misses. The ones that go left, as was the case for Tiger on courses where left had hazards and could potentially knock him out of contention in major tournaments, were “big misses” that he aimed to avoid.

Medicine is also about controlling misses. Not necessarily hitting the ball 300 yards down the middle, but getting on the green safely to have a birdie attempt, not dealing with out of bounds or the need to take drop balls.

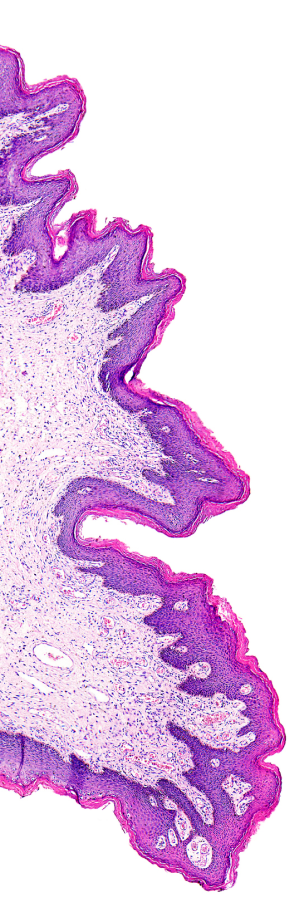

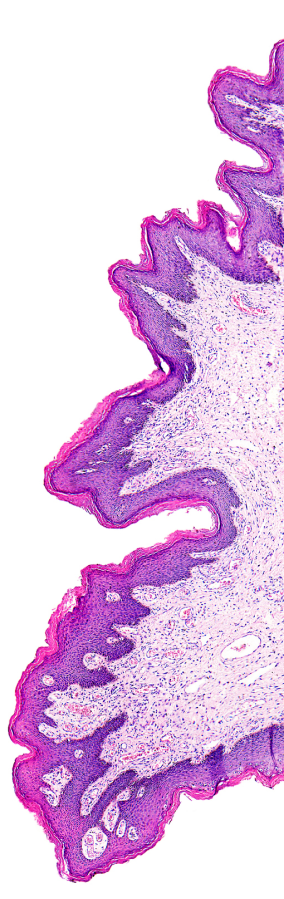

Pathology in particular, I think, is not a lot about hitting big shots consistently, but controlling for errors. We should be expected to recognize “clearly benign” from “clearly malignant” on a slide. The challenges occur when the answer is not “clearly” one or the other. There was a recent article on showing discordance among pathologists for “gray” areas in pathology published in JAMA, and a more recent study showing 20% of diagnoses referred to a referral center were changed, some with clinical significance, published in the breast literature.

Biology is not linear. Tumors do not jump from well to moderately to poorly differentiated, but we make grading and staging schemes linear. We try to take biologic continuums and put them on a line with a constant slope of 1 when in fact the biology is not linear nor are the pathologists. One person’s “moderately differentiated” can be another’s “well-differentiated.” It is part art and part science to eliminate big misses. Just as with atypical ductal hyperplasia and ductal carcinoma in-situ in breast pathology, for example, there are differences of opinion.

The good news/bad news is that we have been at this long enough to know our limitations. While some of the technologies have improved (improved staining and light microscopy, outcomes studies and the like), there will always be some degree of uncertainty.

In addition to the obvious roles for digital pathology for peer review, QA, second opinion, expert consultation and archiving material to compare with subsequent material, perhaps the greatest impact digital pathology will have is removing some of this subjectivity by utilizing quantified analysis and pattern recognition tools.

The use of digital pathology will allow us to have the ability to avoid the big miss -- the decision between whether to remove more tissue or not, the ability to perhaps better predict outcomes beyond light microscopy alone and improve patients' lives with a greater degree of confidence to complete our rounds.

If you liked this post from Dr. Keith Kaplan, subscribe to the blog to receive new blog posts directly in your inbox.