Change Evolution in the Laboratory: IHC to DP

Robin Weisburger

The acceptance of digital pathology and its implementation across the United States have been met with a fair amount of challenges. Many equate digital pathology’s evolution in the laboratory with radiology’s move from film to digital media. Despite obvious advantages like immediate availability of images for viewing and image storage being reduced to computer drives as opposed to rooms full of film, it took time for radiology to convert to using digital media as a routine matter of business. Pathology is experiencing much of the same resistance.

However, resistance to change is not unique to the digital realm. Over the years, as new technologies become available, time and effort must be invested to move beyond traditional methods to reap the benefits of progress.

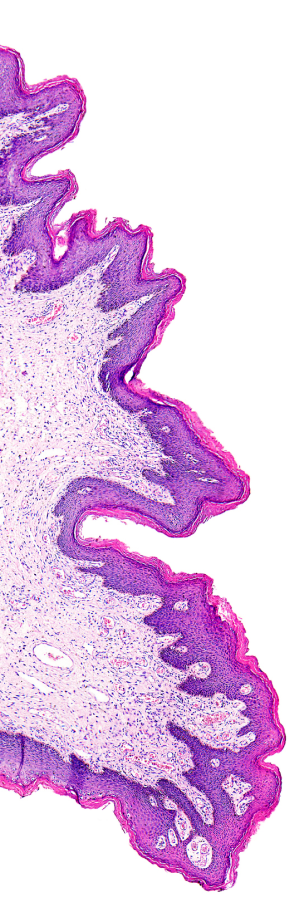

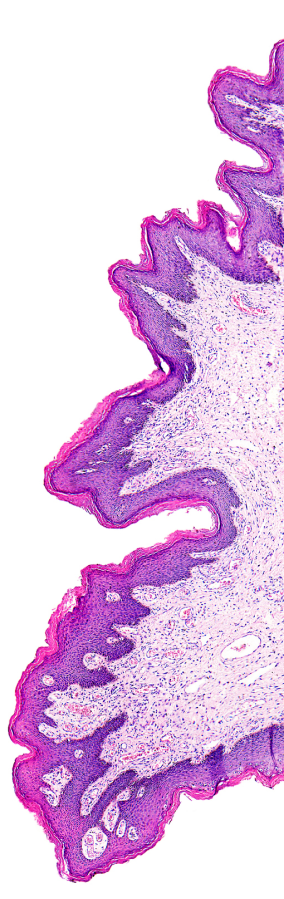

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) is a case in point. A widely accepted and routine methodology for both diagnostic and research applications in pathology, when IHC was first brought into the lab, there were more than a few skeptics.

In the mid-1980’s, I was a new histotechnologist and one of our pathologists decided to engage me in his quest to bring “immunoperoxidase” techniques into our lab. Armed with my diamond marker for circling the tissue sections and makeshift humidity chambers for the staining process, I spent my days in the lab diluting antibodies with PBS (phosphate buffered saline), incubating my slides and staining them with DAB (diaminobenzidine).

Of course, this new technology was met with some resistance. Optimum tissue fixation and processing were vital as was the slide preparation itself. These factors necessitated changes in laboratory practice. Reagents and equipment generated additional laboratory cost, and at least in the early years, the procedure was labor intensive and required dedicated staff to perform it.

Finally, there were pathologists who were slow to adopt this new technology as it required additional training for interpretation, and many were content with their well-established staining protocols. Regulatory agencies required statements on pathology reports reflecting that the procedures were not FDA approved and provided “adjunctive diagnostic information”.

Changing from our familiar and comfortable technologies that have served us well for many years is always difficult. The arguments are similar- cost, time and comfort with how things have “always been done”. Digital pathology is no different. Slide scanners can be expensive, although the cost is coming down. The quality of histology sections directly impacts the quality of the scan, sometimes necessitating greater care and time for preparation. Scanners must be loaded and unloaded, and images must be QC’ed, all requiring dedicated staffing and time. Pathologists must be trained in how to review and interpret their images using this new technology. Finally, at least when used for clinical purposes, regulatory agencies require appropriate validation studies to ensure the quality of the work itself.

However, as with radiology, immunohistochemistry, molecular techniques and other innovations, digital pathology offers a host of advantages once embraced. Cases can be shared, collaborations facilitated, research teams can extend across continents. Now, with artificial/augmented intelligence applications for pathology images, pathologists have tools that can improve their daily workflow with the application of deep learning algorithms.

It will still take time for pathology to realize the full potential of digital applications. Implementation and acceptance of radiology and IHC did not happen overnight. Digital pathology is seeing an evolution that will someday take diagnostics and research to new heights, which for now can only be imagined.