The Paraffin Curtain is Melting

Keith Kaplan, MD, Chief Medical Officer

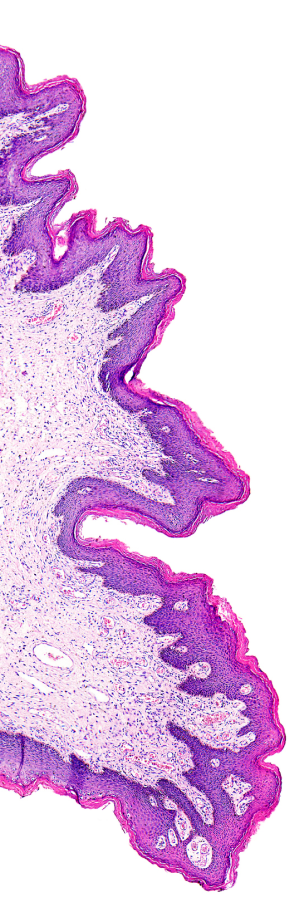

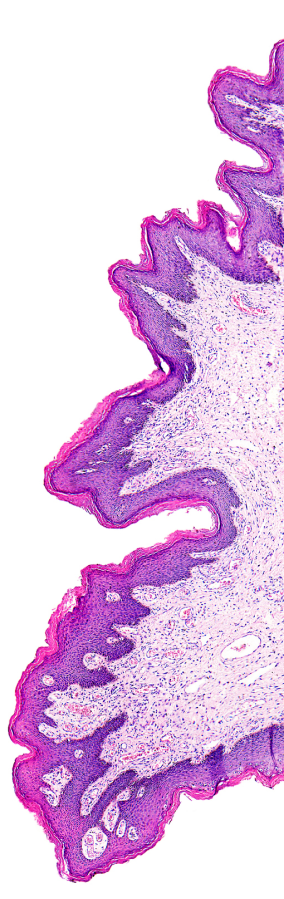

Surgical pathology is increasingly becoming more based in molecular diagnoses rather than morphologic diagnoses. For 150 years, morphology has been an accurate predictor of clinical behavior with standardized criteria for both histological grading and pathologic staging of tumors. While there are certainly “gray areas” in morphology and classification of disease, a traditional approach of classifying tumors based on location, gross pathologic findings and histologic findings combined with immunohistochemistry, over the past 30 years, has served our patients well in terms of classifying tumors for appropriate therapy and management.

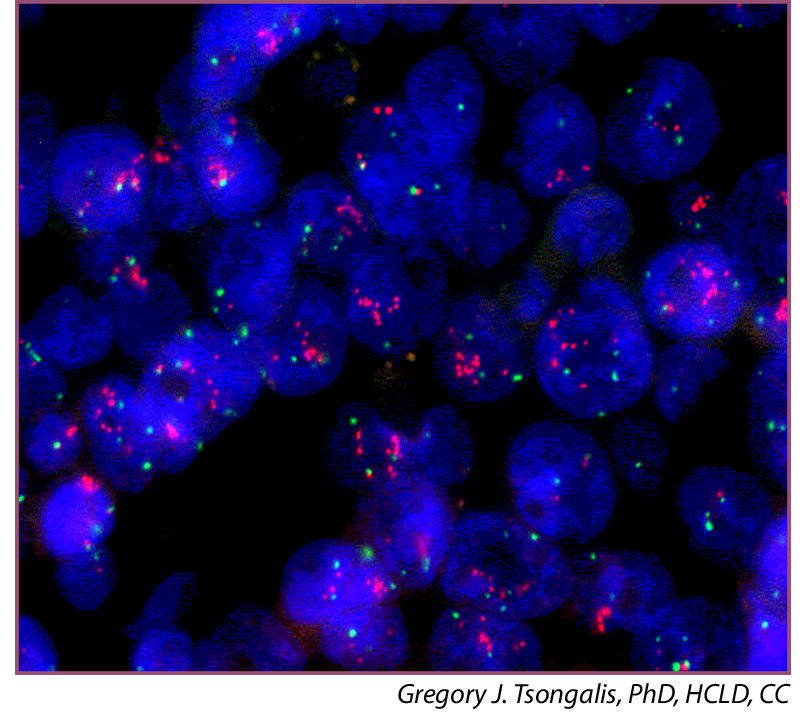

Over the past decade, there has been a rapid increase in knowledge gained toward molecular findings within tumors. Additionally, targeted therapies for those molecular aberrations have started to revolutionize oncologic care for malignant tumors. Dedicated antibodies and target therapies toward specific receptors that may be overexpressed in tumors have dramatically altered the way in which cancers are treated. While the pathologists of yesterday could classify diseases based on gross, microscopic and immunohistochemical findings, the pathologists of today are required to combine those skills in addition to appropriate molecular surrogate testing for appropriate classification and potential targeted therapy.

This change or alteration in arriving at the correct diagnosis and providing reliable, reproducible clinical information has changed the role of the pathologist in the 21st century. Certainly this is not an unexpected outcome as we have understood for many years that our understanding of molecular aberrations clearly plays a role not only within certain categories of tumors but within those categories of tumors. For example, non-small cell lung carcinoma, as a group, morphologically has many similarities. However, their molecular alterations are better predictors of clinical behavior and response to therapy.

Within this changing landscape, pathologists are increasingly being tasked to provide molecular testing or refer adequate tissue for necessary testing from partner laboratories. In fact, the morphologic diagnosis, in some cases, is in my opinion, simply an adjunct for the next step of “reflex molecular testing.” It has been understood for many decades that molecular classification would trump morphologic classification. We are seeing that result today. Rather than the traditional classification of diseases, and tumors in particular, based on organ, location, gross and microscopic findings, the molecular profile may have more significance and importance than the morphological classification on its own.

In fact, I believe that the traditional classification of disease as summarized in tumor atlases and staging manuals will be replaced by molecular classification of disease. While you may have a grade 1 infiltrating ductal carcinoma of the breast or grade 2 endometrioid adenocarcinoma of the uterus, the tumor’s biochemical and molecular profiles will have far more significance than tumor type or grade. While this is welcome news for the advancement of medicine, I believe it fundamentally changes how pathology will be practiced. Pathologists will increasingly be responsible for appropriate tumor selection of fresh gross tissue for molecular analysis rather than histological analysis.

This has introduced an interesting diagnostic shift in clinical practice patterns. Increasingly, pathologists are being required to “do more with less.” What I mean by this is trying to determine histogenesis and adequately sample enough tumor tissue not only for morphology but also for molecular studies. These are increasingly being done by largely minimally invasive or less invasive techniques through image-guided biopsies or endoscopic biopsies. This removes the need for invasive procedures to obtain diagnostic tissue, while still being able to accurately assess tumor type and molecular profile to help determine either adjuvant therapies or the need for surgical intervention.

Heterogeneity among tumors is perhaps the strongest argument for molecular pathology. I believe that H&E morphology and diagnostic histopathology at the moment have a very tenuous hold on cancer diagnostics. As we have seen with our own limitations with H&E and immunohistochemistry, oftentimes panaceas regarding specificity of tissue markers are oftentimes short-lived. I do think that H&E morphology is shortly due to become complacent, outdated, reactionary, and secondary to molecular diagnostics. I am not, however, beyond skepticism or realism, as Edmund Burke pointed out over 200 years ago, “To conceive extravagant hopes of the future is a common disposition of the greatest part of mankind.”

That being said, if Rudolf Virchow were alive today, I think he would be astounded at the progress made in morphologic techniques and diagnostic histopathology to allow for molecular pathology and I do believe with certainty that a molecular diagnosis will replace a morphologic one and the role of slide-based H&E tissue morphology will become a necessary adjunct for molecular rendering.