The Tumor Board, Virtually

Keith Kaplan, MD, Chief Medical Officer

There is a joke among surgeons and oncologists -- the pathologist at a tumor board is like the guy whose funeral that you are attending; you can't do it without him, but you don't want him saying too much.

Nearly 2 years ago, our tumor boards went "virtual". Like billions around the world, we scrambled to get Zoom, GoToMeeting, WebEx and other applications up and running to hear each other’s voices and share screens to show radiology and pathology images. We anticipated that by the Summer or Fall we would be back to "normal".

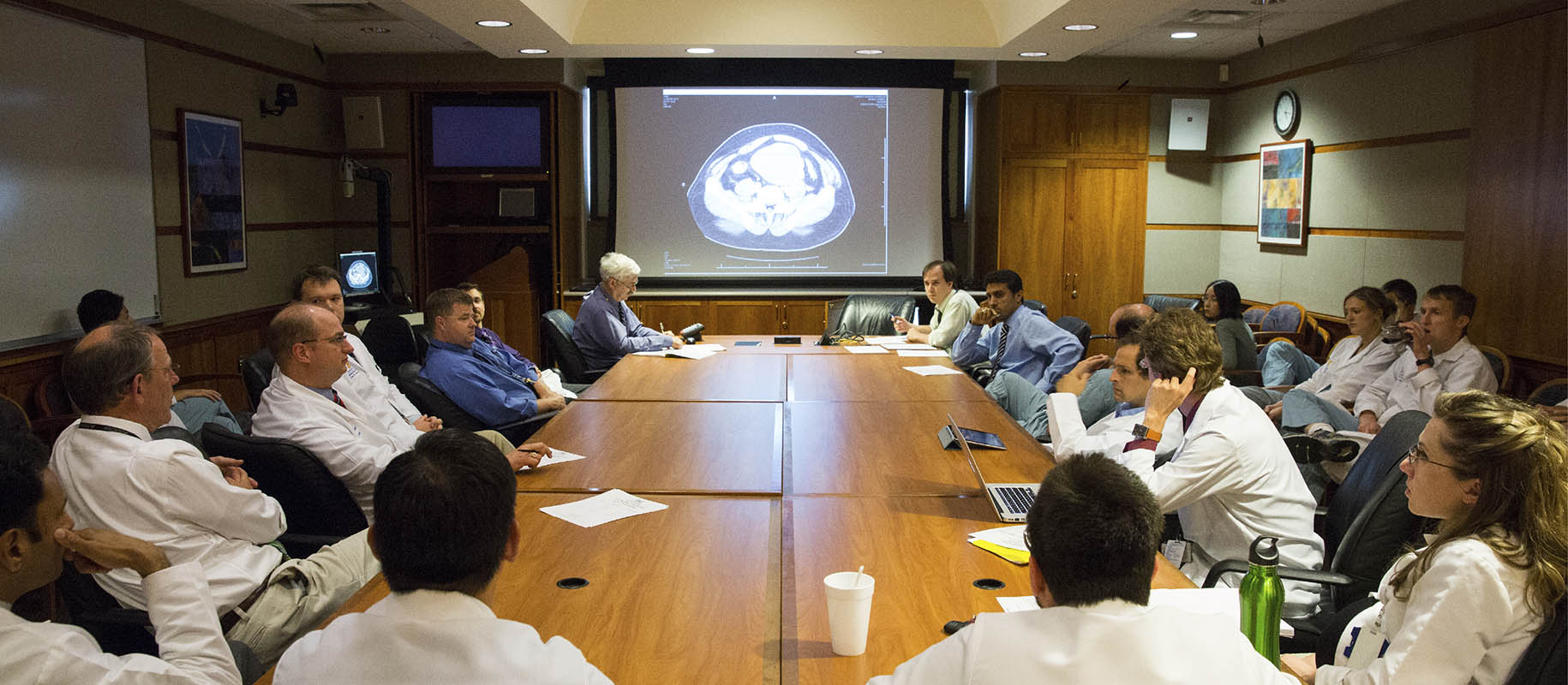

Typically, we would gather in a conference room at 7 AM or 5 PM and discuss cases several times a week in dedicated subspecialty conferences for breast, lung, GI or GYN malignancies, among others. General tumor board, neuropathology and GU cases also had dedicated conferences we attended.

A light breakfast, coffee, light supper and soft drinks would be served, and we would network with each other in person, discuss cases and network some more. Tumor boards are required for cancer center accreditation and necessary for patient management, but they also allowed us to see each other and perhaps discuss hobbies, travel or family.

All that ended in March of 2020. As the line goes in the Eagle's Hotel California song, we all became prisoners of our own devices, locked behind web cams and microphones and cell phones and speakerphones. The ability to grab some coffee and compare notes on stamp collecting, target shooting, train watching or recent travel experiences ended. How someone was making out with their teenager or elderly parent became muted behind the screens and phones of pandemic times.

Of course, classrooms and courtrooms and boardrooms and clubs and societies and tradeshows and conventions also went virtual. From your desktop or laptop, cell phone or tablet, you could attend both a tumor board in Chicago or Boston and a talk on digital pathology in London without ever even thinking about getting in a car or plane. From your basement office, you could attend a meeting, provide patient care or earn CME without having to remember if you have your hospital ID or boarding pass on hand.

Getting to the conference room on a cold January or February morning at 7 AM was a necessary inconvenience, but we all did it and expected others to do so as well. Where else could you get stale bagels and runny eggs at that time for "free"? Similarly, getting out of tumor board at night, in the cold and dark, was similarly inconvenient, but required.

We tried to "restart" "live" or "in person" meetings through the various waves of Greek letters and surges and shortages. Some folks became ill and had to remote in if they could do so. Some were out of the hospital for months, reluctant to do anything "in person" if they could avoid it.

Pathologists, radiologists, surgeons, oncologists, radiation oncologists and medical geneticists started to settle into the new "normal" with personalized backgrounds and improved cameras, microphones and speakers. We became proficient at connecting, remotely. We even snuck in a short conversation about a common philatelic interest or model railroading diorama we made, both perhaps just out of sight of the web cam we were talking into.

By a year ago, virtual conferences were the new normal, and just became “conferences”. But surely this would end. The bitter coffee and overcooked chicken fingers had nowhere else to go but to the tumor board. Then delta and omicron presented themselves, and we remained prisoners of our own devices.

So here we are, nearly 2 years later, and we remain relegated to our own offices and homes for the activities that were once supported by a conference room. Proposals were made to "open up the room", and those who wanted could attend "in person". No one voted to do so.

Perhaps this is the new "normal", showing pathology images from behind a screen. Imagine being a third-year medical student in March of 2020 on your surgery rotation and attending your first tumor board from your attending's speaker phone. Not seeing the interaction of different specialties, the jokes and comments, the side discussions about which ammo is best or who is going to win the election. Just a speaker phone. No runny eggs and day-old Danishes with bitter coffee.

Pathologists are excellent at social distancing. It usually starts at a young age. We do well working on projects, by ourselves, without social interaction. We excel with stacks of slides in a room by ourselves. Not that we can't be the life of the party, but most of us have chosen to be in a supporting role. We lead in assists typically, not in total points.

I, for one, miss these interactions, driving in the blowing snow at 6 AM to sit in a room with other physicians and healthcare professionals and watch them wave their hands, arguing their points and pulling up references on their cell phones to substantiate their arguments. I miss seeing others do the same thing while I wait patiently behind the microscope to show the next case, often talking with the radiologist about their weekend plans or their teenage daughter.

For the pathology residents and fellows of 2020 and beyond, we have an important role in tumor boards, we need to be there, in whatever capacity. Keep your comments brief but on point, and enjoy the discussions. It is critical to interact with your clinicians. You can't do this from behind a monitor and phone. Leave that for virtual courtrooms and boardrooms. Make sure you are not a voice with a good-looking pathology image.

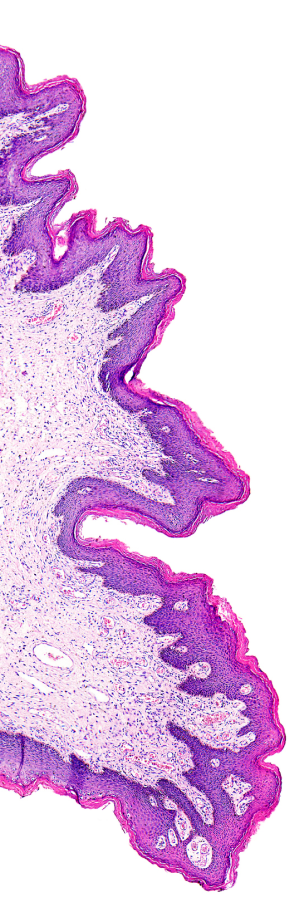

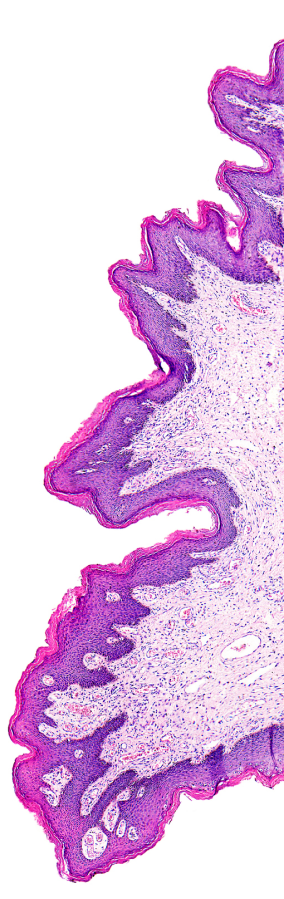

Pathologists today compared with yesterday have a critical role to play in patient care. Never before in the history of pathology have we been tasked to do as much as we do with smaller biopsies and excisional specimens. With those specimens, we are stewards of the tissue and responsible for appropriate selection of immunohistochemical stains while trying to conserve tissue for next-generation sequencing.

It is now more important than ever, with a nationwide shortage of pathologists and increased demands on turn around time and reporting for healthcare institutions, that we communicate with our clinical colleagues, in forums such as tumor boards, about the importance of appropriate biopsy, evaluation and necessity for enough tissue for patient care.

We must have a seat at the table at the tumor board and perhaps have a louder voice than we have had traditionally, albeit virtually. Without doing so we risk simply being report generators from the colloquial black box of the laboratory without the appropriate discussion for best outcomes.