What Does the Gene Panel Show?

Keith Kaplan, MD, Chief Medical Officer

Recently I received a call from an oncologist. After giving me the patient’s name, she asked “What does the gene panel show?”

I responded we didn’t have the patient’s biopsy yet, that he was scheduled to undergo a CT-guided needle core biopsy, and we would process it overnight and review tomorrow as we normally do.

The oncologist acknowledged the patient was undergoing the biopsy in the afternoon, and we hadn’t even yet done an immediate fine needle aspiration rapid on-site assessment prior to the core biopsy.

But she needed the gene panel.

I asked if the patient has a history of malignancy, as she was an oncologist and was calling about this case. There was no prior history of malignancy. She wondered when we would have the gene panel.

I informed her that we would review the biopsy and determine, if there was malignancy, if there would be adequate tissue for additional molecular testing as indicated.

She told me to call her with the results of the gene panel by tomorrow.

I asked the oncologist how does the patient already have an oncologist when there is no history of malignancy. She said she was consulted. She said it is likely the patient has a sarcoma or lymphoma given the PET scan.

“Really?”, I asked. “What kind of lymphoma or sarcoma?” I continued.

The oncologist replied, “We will get that from the 500 gene panel.”

I continued “So, the patient has a malignancy, likely not a carcinoma, but a lymphoma or sarcoma, and the gene panel will tell you what kind?”

“Yes”, the oncologist offered.

“Hmmm, that’s interesting, I will let you know when I get the biopsy”.

This phone call, in several iterations, has been taking place between oncologists and pathologists for decades. However, years ago, there was generally a referral to an oncologist after a malignant diagnosis was made for appropriate staging, treatment and management given other co-morbidities, patient’s general health, treatment options and of course how aggressive or non-aggressive a particular patient wanted to be about treatment (or not).

Estrogen receptors, progesterone receptors and later Her-2/Neu were among the first biomarkers with targeted therapy, then of course CD117, later EGFR, ALK-1 and ROS genes, to name a few. If you went to the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) five or six years ago everything was “PDL-1”. Posters, talks, booths, dinners, events and late-night bar gatherings were touting and celebrating PDL-1 and the targeted therapies from early morning to late at night. Multi-gene panels were less prominent but a presence.

Today, next generation sequencing offers oncologists, and their patients, perhaps more options in better guiding conventional therapies and/or directing targeted therapies.

When you consider how far we have come so fast since sequencing the human genome, this is an exciting time. Cancers that had limited survival in the past are increasingly treatable while allowing people to be productive beyond debilitating effects of surgeries and systemic therapies.

In my practice lifetime, some breast cancers, for example, will be a non-surgical disease, the mainstay of therapy for over a century since Halsted going back to 1894.

As a medical student, I watched dozens of radical mastectomies and lymph node dissections, with chemotherapy and radiation and complications from the surgery and treatment. ER and PR were in their infancy. HER2 was to come.

As a pathology resident, I saw radical mastectomies get replaced by small lumpectomies and occasional nipple sparing mastectomies. Debilitating axillary dissections were replaced by sentinel lymph node biopsies and an understanding of what isolated tumor cells versus micro-metastases versus macro-metastases mean.

Now, some types of breast cancer will not even have surgery as a mainstay of therapy.

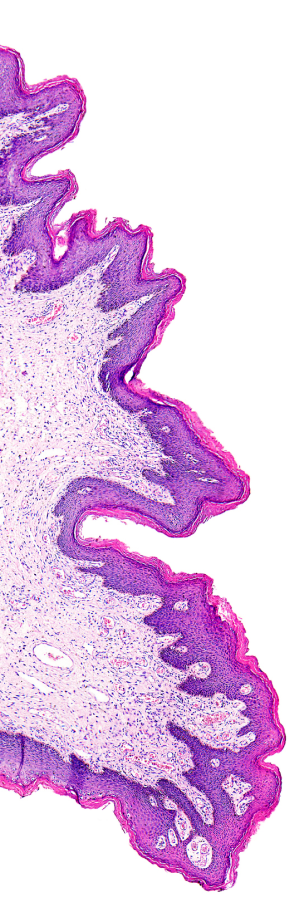

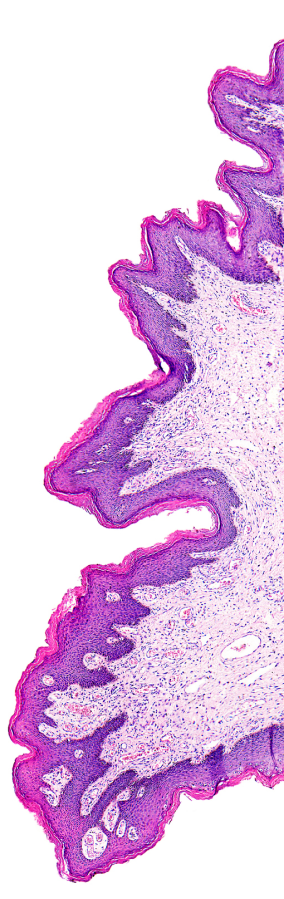

While our understanding of molecular alterations continues to develop, however, I hope that our clinical colleagues still appreciate the role that pathologists will have in conjunction with molecular testing, keeping morphology at the core of diagnosis for appropriate treatment.

Considering that the vast majority of biopsies are benign, this partnership will be required. To assess what treatment is appropriate for what disease process will continue to require expensive testing to further characterize tumors beyond histology. In the recent update to the classification of brain tumors, molecular phenotyping is a critical factor for diagnosis. It has become standard of care, as it has with lymphoma classification.

We must continue to ensure that the morphology guides the appropriate molecular analysis as these technologies, knowledge and treatments continue to progress.

I called the clinician back the next day after reviewing the core biopsies on her patient. I let her know the biopsy showed caseating granulomas. I would stain the tissue for mycobacterial and fungal organisms, but the differential diagnosis includes many entities.

The oncologist said she would get infectious disease to see the patient but asked if we could send the tissue for PCR for tuberculosis…