What Will Our Legacy Be?

Keith Kaplan, MD, Chief Medical Officer

My maternal grandfather was a glazier. He was orphaned at a young age and raised in an orphanage on the West side of Chicago with 2 brothers. One of those brothers died during adolescence. My grandfather and his oldest brother fought in World War II and became part of America’s Greatest Generation. He and his brother started Chicago Glass which became the largest glazier company in the city. For over 30 years, my grandfather hung glass on some of the tallest buildings in the world at the time. Sears Tower, John Hancock, Lake Point Tower, Standard Oil, you name it, he worked on it. Buildings downtown had to be “glassed in” by November 15 if the electricians, plumbers, elevator, drywall and carpet guys were to have a chance to work through the winter for spring occupancy on a residential or commercial high rise. In the winters, my grandfather drove a cab between “indoor” jobs such as hanging mirrors, repairing windows or building storm windows. He would drive me around in his large Checker cab and point out what buildings he worked on and what he did, what worked and what didn’t, if he got injured, or one of his men did, and when they “glassed” it in.

I tried to keep mental notes of all the buildings, but they were too numerous. I tried to remember landmarks and such. He told me his fingerprints were all over those buildings. The window washers high above the streets preserved his work. Of those buildings I do remember, I can point out to my family and tell them my grandfather, their great grandfather, installed those windows and lobby doors. The glass reflecting the city and the river that winds through it were in part due to him, hand cutting large panes of glass to line offices, conference rooms and observation decks. In medical school I would run past several of the buildings, just to make sure none of the glass popped out. One of his last jobs involved putting the lobby glass on the Daley Center, then taking that glass out and putting in stunt glass for The Blues Brothers, then replacing the original windows. I would go check out The Picasso and the lobby glass.

Pathologists have fewer tangibles to point to and say, “I did that” or “I built that”. Our product is surgical pathology reports and laboratory reports. There was a time these were typed in triplicate with carbon copy paper, with one report going to the patient’s physician, one to medical records and one kept in pathology. The reports would then get bound up into volumes that lined the shelves of the department library/conference room. Increasingly, of course, these volumes have become “electronic”, flowing to patient portals and physician EMRs. So now there aren’t even volumes of books to point to as having created. The reports are in the LIS and EMR and on patient phones, but there is nothing I can point to.

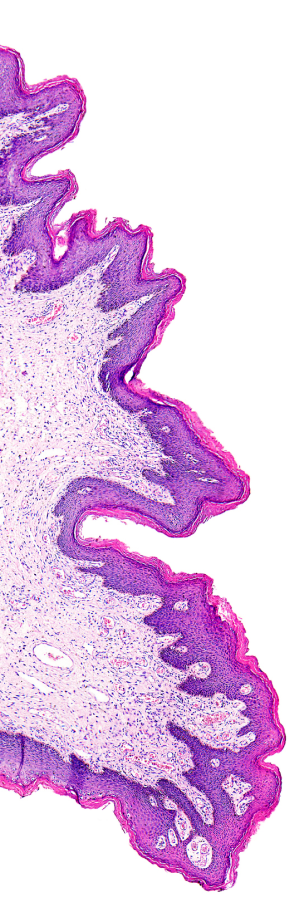

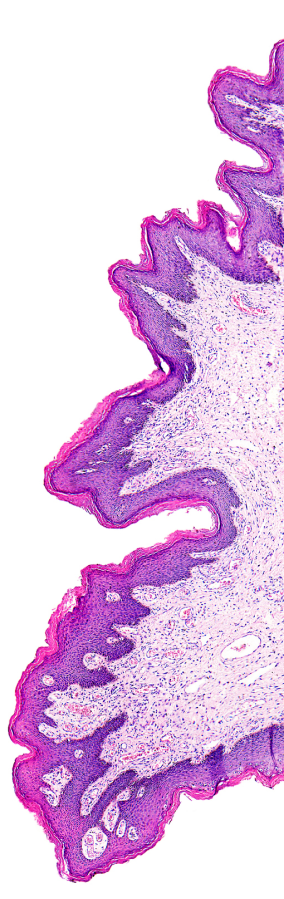

Increasingly, laboratories and pathology groups are adopting digital pathology. As this transformation occurs, what will our legacy be?

What will be the story told in 50 years, 100 years, like those that my grandfather told me from the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s that I try to pass on?

What will future generations see with digital pathology that we did not? What treatments and cures will be discovered by moving away from conventional light microscopy and into whole slide scanning combined with next-gen sequencing (NGS) and artificial intelligence? The reports of today contain a host of data with the latest immunohistochemistry, molecular diagnostics and NGS.

What will pathology reports look like in 50 years? In 5 years perhaps? Pathologist offices will of course look different. Multiple monitors will replace a single one next to a microscope sitting on top of an old dermatopathology or pediatric pathology textbook to obtain the proper height.

The pathologists, engineers and manufacturers/vendors who have worked to make digital pathology simply pathology will leave a legacy as strong and stunning as glass on a high-rise building. With the strong foundation that has already been created, the ability to see beyond the light microscopic level will in so many ways revolutionize health care.

Pathologists will use their hands less and their eyes more, analyzing more data in less time with improved efficiency and accuracy combined with improved prognostics and therapeutic diagnostics across a global network. Limiting ourselves to the microscope will appear like that scene in the 1986 movie, Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home, where Dr. Leonard McCoy travels back to the 20th century and comments on the medical procedures he finds there, proclaiming, “That’s barbaric!”.

This generation will be able to look back and say, we built that, we did that, we improved care and improved human lives, and we left this floating rock better than how we found it.

In time, for those of us in this industry, we won’t be able to point out the window from a Checker cab and say “I did that”, but we will be able to ensure those looking out those windows from their offices or homes high above the street, river and lake, will have improved diagnostics, prognostics and therapeutics to enjoy those views even more.