Who’s looking at your digital atlas?

Corista

In the pre-PowerPoint era of the 1980s, armed with a carousel filled with 35mm slides, I traveled the country giving an introductory presentation on ploidy and cell cycle analysis. We now lightheartedly refer to this period as my “What’s a pixel? talk” years. To create the slides, I sketched out the layout for each on a sheet of copy paper, and then faxed them to Houston where a delightful gentleman named Jim would magically create the Kodachromes. This usually involved a phone call or two to talk about colors and fonts, following which Jim would mail the slides to me a week or two later.

Fast-forward to today, and the power of the graphics presentation has morphed into something that is instantaneous, at our fingertips, within our control to customize at a moment’s notice, flexible – and much more powerful than at any previous time. We now easily incorporate animated graphics and even sound. The desktop publishing revolution saw the convergence of hardware and software to create disruptive products that put previously out-of-reach tools into everyone’s hands.

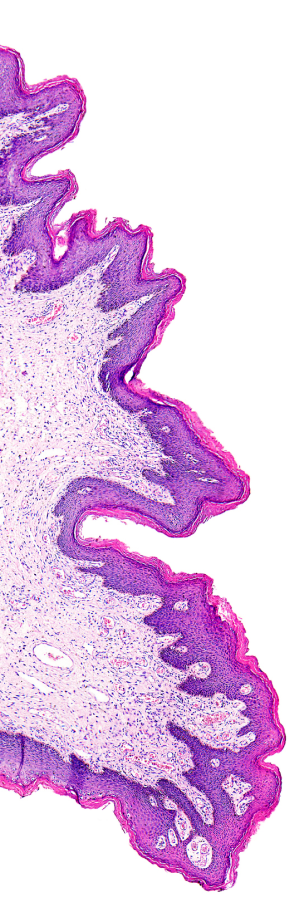

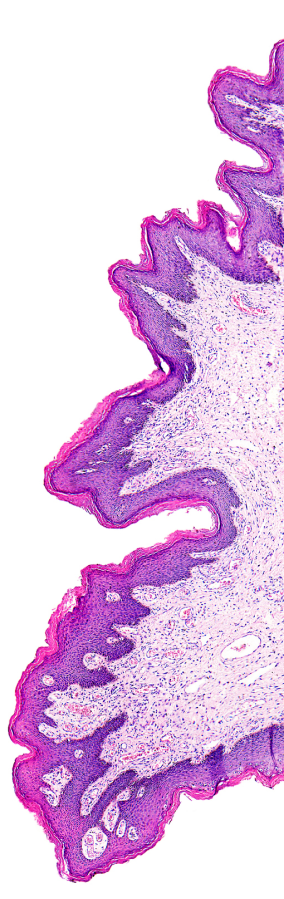

We don’t need to look hard to find similar revolutionary examples within our own labs, where the digital atlas illustrates a clear parallel. The classic pathology atlas, which usually focused on a specific body system such as GI, respiratory or CNS, was used for education or to assist when faced with a difficult diagnosis – two examples of the latter being “look-alikes” and rare entities. Once reserved for static snapshot images, and published in finite bound books that aged while sitting on a shelf, digital atlases have now exploded in both power and utility.

A whole slide image (WSI)-based atlas removes all the boundaries and inflexibility of its rigid hardbound forerunner. Creating a digital atlas is within reach of us all. This dynamic tool still aids in both education and assisting with difficult diagnosis, but varies dramatically from its predecessor in the amount of information captured per image, image source(s), its virtually unlimited capacity – particularly if cloud storage is incorporated – and its ability to be shared both internally and externally with complete disregard for geographic boundaries.

The most obvious difference is access to the entire digital slide, so the diagnostic entity may be viewed in context of its surrounding morphology. This is as opposed to the restrictions imposed in the typical individual 40x H&E “field snapshot” on the glossy page of a classic atlas.

But the benefits of digital don’t stop at the obvious. A digital atlas can incorporate patient metadata and image annotations – both of which can be easily turned on or off for educational purposes. You also have the ability to make morphometric measurements on the images – and since space is no longer a barrier – add as many supplementary slides as desired, including special, immuno and molecular stains.

Sort, categorize, test, compare, share, annotate, edit, revise and endlessly expand.

Using a digital pathology platform such as Corista’s DP3, which is scanner agnostic, you can incorporate WSI from all the different scanners within your network – or add images from anywhere. This translates into the ability to bring in numerous “authors” from within your department or from around the world. Unlike a physical one, a virtual digital atlas can incorporate the expertise of hundreds or even thousands of experts.

While some of us focus on entire body systems, and others on a particular organ or even an individual entity – most of us have a favorite diagnostic area where we excel. The digital revolution gives each department, and each pathologist, the power to stake their claim as an expert – and the reach of the Internet allows each of us to easily share that expertise worldwide.