Proficiency Testing in the Digital Pathology Age

David C. Wilbur, M.D.

Don’t get me wrong based on the title; I am not advocating for proficiency testing (PT). After Medical Boards, Resident In-Service and Board exams, I never thought I would be thinking about any more testing at all. There are better ways to test for ongoing real proficiency. Exercises that test “real-world” skills, such as focused review of signed out cases or concurrent reviews - with feedback – not only lead to better outcomes (patient safety) but also improve practice (constructive feedback). But testing is an unfortunate part of modern life. It’s a metric, and regulators like metrics. For years we dealt with the specter of impending gynecologic cytology PT. Based on the complexity of the federally mandated glass slide testing format, the organizations capable of producing such a monumental effort appeared to reach a détente with CMS, and no testing took place for many years after the federal regulation went into effect. However, when one organization came up with a program, the seeming détente was at an end, and CAP and ASCP were essentially forced to enter the fray.

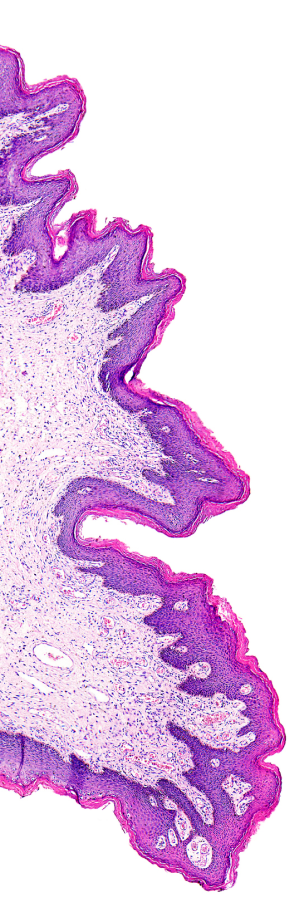

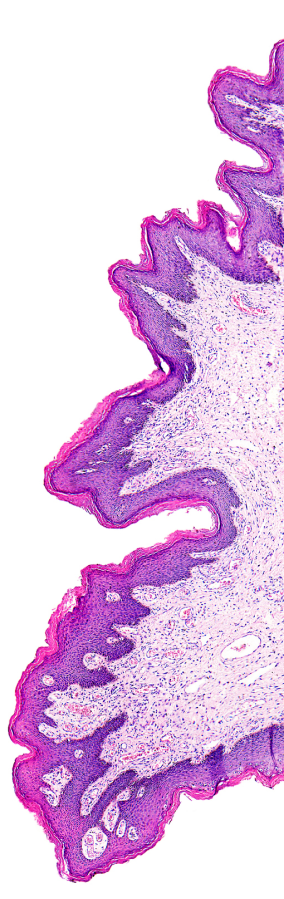

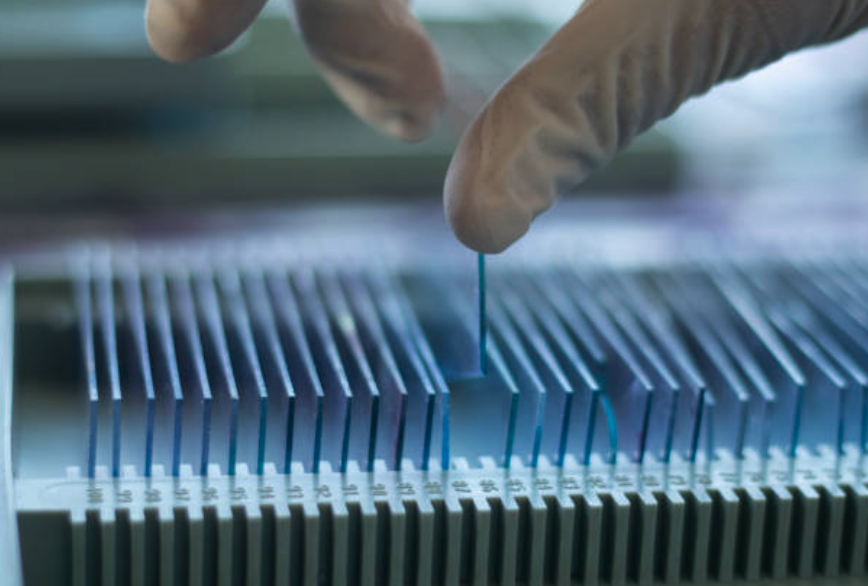

Being on the CAP Cytopathology Resource Committee at the time, I can attest to the complexity of running a glass slide-based proficiency testing program. First slides needed to be obtained. This requires laboratories to submit slides, either retired or current (the latter with a mechanism for retrieval if required for patient care). Groups of 20 or more pathologists convene in a hotel conference room for 4 days, 4 or more times per year, to review cases for entry into the program. Thousands of slides are reviewed at each session. A significant percentage are rejected as poor examples not fit for proficiency testing. For accepted slides, a fee is given to the submitting lab as an incentive to send more. As an aside, many labs use these fees to send cytotechnologists to annual meetings such as ASC (a real benefit of the program), while others bank the cash. You might think the logistics of the program ended there – but wait – are slides accepted by the committee a statistically valid challenge? One might cause a loss of livelihood for the unfortunate outlier of a missed HSIL in a difficult case! So, slides have to be field tested and “validated” to a reasonable standard. At CAP this was done in the non-PT cytology educational challenge program, a non-PT lab accreditation exercise in which most labs in the US participate. Slides achieving a reasonable “correct” rate can then enter the PT program.

While the above is the slide entry process (a non-trivial task), there is also the logistical issue of maintaining the slides – they need to be catalogued, stored, retrieved, cleaned, configured into sets, shipped, and returned. Examinations need to be given in laboratories, proctored and monitored for fair evaluations to take place. The validated slides, therefore, become very valuable indeed! Unfortunately, we found that some slides get lost, some are broken, some are never returned and lastly, as statistics are retallied after each subsequent reading, some slides fall out of validation. Thus, the pool of validated slides needs constant replenishing, and the cycle of need continues. Overall, this is a very complicated and expensive process, AND, since federally mandated PT testing can lead to loss of the ability to practice, it’s a stressful experience for the testee.

So, how can digital pathology help? The use of digital content – whole slide images – instead of analogue glass slides - changes the playing field for PT profoundly.

Digital slides:

1) can be reproduced in unlimited numbers, with each slide being identical;

2) can be transmitted over the internet nearly instantaneously;

3) and, can be accessed from any workstation with high-speed internet access.

Given these key features, one can immediately see that for a 10-slide test, the minimum number of validated slides necessary is only 10! A PT testing event could be done all in one day, at one time, for every individual in the country. Of course, more slides would be needed to add unique PT tests for those sick or on vacation. However, the number of slides needed is no longer in the thousands, but an order of magnitude less. In addition, the digital slides used would be stored on servers, never lost, never broken, and never need cleaning. Slides would be sent to labs electronically and could even reach participants in their homes if necessary. Answers could also be submitted immediately via the internet, and scoring and reporting performed automatically.

PT using digital methods is not a new idea. Some have proposed using WSI or individual digital photomicrographs for gynecologic cytology testing (1,2). Some digital PT efforts have already been implemented. In Canada, issues with breast cancer markers in surgical pathology have led to WSI PT on breast histology-based special studies (3). In a 2007 study of digital cytology, one group proposed WSI for gynecologic cytology (4) but concluded that although in a controlled setting the testing was accurate, they opined that the then current technology might not be ready for a fair national test. The primary negative issues were the 3-dimensionality of the specimens and the lack of fast or intuitive interfaces for users. CMS even made a proposal nearly a decade ago to change the federally mandated gynecologic cytology PT program to a digital format. The idea was dropped for a variety of potential reasons, most likely those noted above, but also because the regulations mandated a “glass-slide” challenge (in order to mimic real life), and therefore the regulations would need to be changed – a non-trivial process in itself.

So, what has changed and where is the state of digital PT today? First and foremost, the technology has advanced. For cytology, z-stacked or multiple plane images, are now easily obtained making the 3-dimensional nature of the specimen a non-issue. For all types of specimens, the user interfaces have been refined and are easier to navigate. And finally, as the use of digital pathology has increased in routine practice for teleconsultation, primary interpretation, education, and research, experienced users will be more accustomed to additional exercises (i.e. PT) at their workstations.

What might be the ways digital PT will be implemented? As many residency programs now implement in-training digital challenges for students, sets of slides could be prepared within institutions or by national organizations in all areas of surgical pathology. Subspecialty pathologists could take these challenges at their leisure in voluntary PT or as mandated (unfortunately) by licensing/privileging bodies. Federally mandated gynecologic cytology PT could again be considered for a digital transformation. Technology, user interface, and experience issues have made this more feasible over time, and significant cost and labor savings could be realized with such a change.

Just as all types of digital pathology implementation will continue to increase (albeit slowly) in US laboratories, use cases will continue to expand and these will undoubtedly include PT. Eventually, improved cost-effectiveness, far better statistical slide validation, ease of distribution, and higher levels of user acceptance (as well as regulatory enthusiasm for metrics), will drive moves to further implement digital PT.

1) Marchevsky AM, Wan Y, Thomas P, Krishnan L, Evans-Simon H, Haber H. Virtual microscopy as a tool for proficiency testing in cytopathology: a model using multiple digital images of Papanicolaou tests. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2003;127:1320-4.

2) Demichelis F, Della Mea V, Forti S, Dalla Palma P, Beltrami CA. Digital storage of glass slides for quality assurance in histopathology and cytopathology. J Telemed Telecare. 2002;8:138-42.

3) CADQAS: Digital Interpretive Proficiency Testing. https://cadqas.org/testing.html (accessed 2-28-2022)

4) Stewart J 3rd, Miyazaki K, Bevans-Wilkins K, Ye C, Kurtycz DF, Selvaggi SM. Virtual microscopy for cytology proficiency testing: are we there yet? Cancer. 2007;111:203-9.