Part 3: A Timeline of Global Pathology Initiatives

Robin Weisburger

This article is the third in a four-part series highlighting the evolution of digital pathology and its impact on the access to pathology services throughout the world. If you missed it you can find Part 1 here and Part 2 here.

Digital pathology technology is advancing at a rapid pace offering solutions to the increasing need for pathology services. In concert, initiatives utilizing this technology are becoming more and more common to improve accessibility to pathology services worldwide.

For some countries, lack of financial resources has limited access to many pathology resources. More recently, however, digital consultations are becoming a realistic option for these regions as costs for whole slide imaging decrease and internet access improves. Local health facilities can potentially provide basic access to pathology testing which can then be referred to regional or referral hospitals.1

The following timeline offers some highlights of the use of digital pathology at the international level in the last 25 years.

1992-1998: Réseau Internationale de Télémédicine (RESINTEL)- provided “static telemicroscopy” services for isolated areas of France as well as hospitals in India, the Middle East, Morocco and several countries in Africa. Still images captured by video cameras attached to microscopes were transmitted via a network that evolved from a telephone based communication system to a satellite system.2

1994: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology (AFIP) began providing digital consultation services to Brazil, Mexico and South Africa using static photomicrographs transmitted via the internet.3

2000: The International Union Against Cancer (UICC) established a Telepathology Consultation Center (UICC-TPCC) in Berlin, Germany to provide diagnostic support to pathologists worldwide. Using store and forward technology, images and clinical data were submitted over the internet to the UICC-TPCC server. The TPCC would then transfer the case to an affiliated international expert for their review and interpretation.4

2001: Arias-Stella Pathology and Molecular Biology Institute in Peru and the Instituto Nazionale per lo Studio e la Cura dei Tumore in Milano, Italy began using static telepathology to perform consultations between the two countries. The Generic Advanced Lowcost transEuropean Network Over Satellite (GALENOS) was also formed. This network supported dynamic intraoperative telepathology in 14 clinics in Bulgaria, France, Germany, Greece, Italy and Tunisia using remote controlled robotic microscopes on a satellite network with a 2 Mbps interface.5

2002: iPATH, an open digital pathology platform developed in Basels, Switzerland, was implemented. Linking experts in Switzerland, Germany and Italy to South Africa, Tanzania, the Solomon Islands and other developing regions of the world, it eventually served more than 150 user groups around the world.6, 7

Also in 2002: The United States’ worldwide Military Health Care System (MHCS) used robotic microscopy to perform remote intra-operative consultations between small remote hospitals and Heidelberg Army Hospital in Germany, Walter Reed Army Medical Center and the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, both of the latter in Washington, DC.

Software installed both on a PC connected to an automated microscope at the remote location and on the consulting pathologist’s PC in the expert center communicated via the internet. The consulting pathologist could control the microscope to view the image at the remote location. This successful study validated the use of telepathology for frozen section diagnosis to support surgical services at remote hospitals and laid the groundwork for additional clinical applications throughout the MHCS.8

2004: University Health Network (UHN), an academic medical center in Toronto comprised of three sites, began using robotic microscopy in a dynamic server-client system to perform frozen sections in the absence of an on-site pathologist.

2006: UHN began using whole slide images viewed on their own network. Pathologists connected directly with the scanner’s computer and viewed the slide images from their office workstations. This model also permitted simultaneous viewing of images from multiple workstations if consultation with colleagues was needed.9

2010: UHN established Canada’s first telepathology system linking remote northern hospitals to UHN for subspecialty support.10 Since then, UHN has also begun providing pathology consultation services to Kuwait.11

Also in 2010: University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) partnered with the Second Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University. This program supported diagnostic consultations and quality initiatives as well as educational and research opportunities. In its first five years, the program expanded to include several other partner hospitals throughout China and had reviewed more than 2200 international clinical cases.12

2011: The international open access forum, Medical Electronic Consultation Expert System (MECES), a platform utilizing whole slide images (WSI) and Web 2.0 technologies, was launched. Utilized by the Virtual International Pathology Institute (VIPI), it provided a flexible information exchange for clinical, educational and research use.13, 14, 15

Also in 2011: the Pathology Quality Control Center of China and Ministry of Health implemented a nationwide digital pathology consultation and quality control program in China. Cases were submitted with WSI to a web-based consultation platform. Experts accessed the cases stored on the server via the internet and provided their diagnoses, second opinions or quality assessments as requested. After two years of operation, more than 16,000 cases had been submitted. The consultation service had a turn-around-time of less than 48 hours and realized a 40% improvement in cancer diagnosis.16

2012: Partners In Health and the Dana Farber/Brigham and Women’s Cancer Center collaborated with the Rwanda Ministry of Health to establish the Cancer Center of Excellence (CCOE) at Butaro District Hospital. The first rural based specialty referral facility in East Africa, the CCOE provides pathology services for patients throughout Rwanda and neighboring countries.17

Also in 2012: KingMed Diagnostics in China and the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center established a partnership to provide an international digital pathology consultation service using whole slide images transmitted via a telepathology portal. A review of this service after three years demonstrated improved quality of care for patients in China. Diagnoses were revised in 51% of the cases reviewed. 64% of these revised interpretations were cancer diagnoses.18

2014: UCLA Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine and China’s Centre Testing International Corporation created a joint clinical laboratory in Shanghai offering sophisticated laboratory testing not readily available in China. In addition to providing specialized teaching and training exchanges between UCLA and Chinese pathologists, physicians in China are able to consult with UCLA pathologists on complex pathology interpretations.19

2016-2018: The American Society of Clinical Pathology (ASCP) announced that the Butaro Center of Excellence implemented a cloud-based system to upload WSI of patient biopsies. Diagnoses are now received from pathologists in the United States within 24-72 hours.20 This effort is ongoing, and the ASCP-led Partners for Cancer Diagnosis and Treatment in Africa continues to expand its initiative to include other sites in Sub-Saharan Africa including Rwanda and Tanzania.21

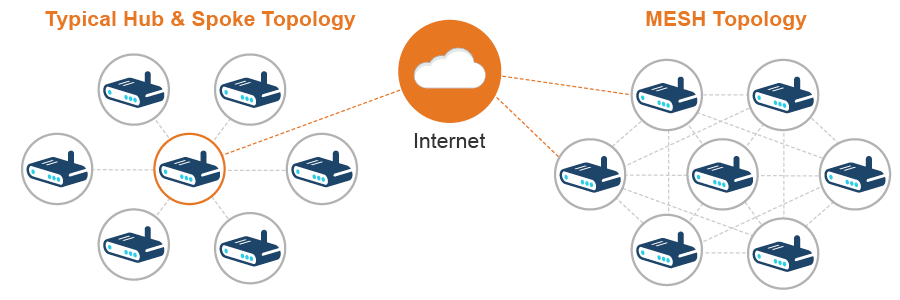

As these networks continue to expand, scalability becomes a key factor in providing pathology support whether on a local or international basis. Early networks communicated via dedicated lines between an expert center and the remote hospitals and laboratories it supported. These Virtual Private Network (VPN) connections still serve smaller networks well.

Other configurations have been developed to support more complex networks. Hub and spoke models allow multiple sites to connect to an expert center. Pathologists at the expert center provide subspecialty support and remote assistance for frozen sections and multidisciplinary team meetings at the other facilities within the network.

Mesh networks expand communications between all sites within a network, improving user access, image rendering and turn-around-time of reporting. Experts can be located at any site, and they are accessible to all users. Sub-specialties experiencing severe personnel shortages such as pediatric and neuro-pathology can collaborate with their colleagues no matter where they are located.

With the global shortage of pathologists, digital pathology technology facilitates collaboration, sharing and consultation on difficult cases with subspecialty experts worldwide. In addition, pathologists can benefit by the sharing of best practices and using their digital pathology platform for education and research at an international level.

Stay tuned for Part 4: Challenges to providing a digital pathology service at an international level.

- Fleming K, Naidoo M, Wilson M, Flanigan J, Horton S, Kuti M, Looi LM, Price C, Ru K, Ghafur A, Wang J, Lago N. An Essential Pathology Package for Low- and Middle-Income Countries.American Journal of Clinical Pathology. 2017; 147 (1): 15-32.

2, 3, 5, 6, 10, 14. Park S, Parwani AV, Aller RD, Banach L, Becich MJ, Borkenfeld S, Carter AB, Friedman BA, Rojo MG, Georgiou A, Kayser G, Kayser K, Legg M, Naugler C, Sawai T, Weiner H, Winsten D, Pantanowitz L. The history of pathology informatics: A global perspective. Journal of Pathology Informatics. May 30, 2013; 4:7.

- Dietel M, Nguyen-DobinskyTN, Hufnagl P. The UICC Telepathology Consultation Center, A Global Approach to Improving Consultation for Pathologists in Cancer Diagnosis. Cancer. July 1, 2000. 89(1), pp187-191

7, 15. Kayser K, Borkenfeld S, Djenouni A, Kayser G. History and structures of telecommunication in pathology, focusing on open access platforms. Diagnostic Pathology. 2011; 6:110.

- Kaplan K, Burgess J, Sandberg G, Myers C, Bigott T, Greenspan R. Use of Robotic Telepathology for Frozen-Section Diagnosis: A Retrospective Trial of a Telepathology System for Intraoperative Consultation. Modern Pathology. 2002; 15(11): 1197–1204.

- Andrew J Evans, Runjan Chetty , Blaise A Clarke , Sidney Croul , Danny M Ghazarian, Tim-Rasmus Kiehl , Bayardo Perez Ordonez , Suganthi Ilaalagan , Sylvia L Asa. Primary Frozen Section Diagnosis by Robotic Microscopy and Virtual Slide Telepathology: The University Health Network Experience. Human Pathology. 2009; 40, 1070–1081.

- Tetu B, Evans A. Canadian Licensure for the Use of Digital Pathology for Routine Diagnoses One More Step Toward a New Era of Pathology Practice Without Borders. Archives of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine. March 2014.Vol 138, pp 302-304.

- UCLA Health: International Telepathology. http://pathology.ucla.edu/workfiles/Clinical%20Services/Telepathology/InternationalTelepathologyFlyerEnglish_FinalMay2015.pdf

- 13. Farahani N, Riben M, Evans, AJ Pantanowitz, L. International Telepathology: Promises and Pitfalls. 2016; 83(2-3): 121-6. Epub 2016 Apr 26.

- Chen J, Jiao Y, Lu C, Zhou J, Zhang Z, Zhou C. A nationwide telepathology consultation and quality control program in China: implementation and result analysis. Diagnostic Pathology. December 19, 2014; 9(Suppl 1): S2. https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-1596-9-S1-S2

- Mpunga T, Tapela N, Hedt-Gauthier BL, Milner D, Nshimiyimana I, Muvugabigwi G, Moore M, Shulman DS, Pepoon JR, Shulman LN. Diagnosis of Cancer in Rural Rwanda: Early Outcomes of a Phased Approach to Implement Anatomic Pathology Services in Resource-Limited Settings.American Journal of Clinical Pathology: 2014; 142(4): 541-545.

- 18. Zhao C, Wu T, Ding X, Parwani AV, Chen H, McHugh J, et al. International telepathology consultation: Three years of experience between the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center and KingMed Diagnostics in China. Journal of Pathology Informatics. 2015; 6:63. http://www.jpathinformatics.org/content/6/1/63

- Partners for cancer diagnosis and treatment in Africa telepathology lab goes live in Rwanda. ASCP One Lab. November 2, 2016. http://labculture.ascp.org/community/news/2016/11/02/partners-for-cancer-diagnosis-and-treatment-in-africa-telepathology-lab-goes-live-in-rwanda

- https://www.ascp.org/content/docs/default-source/get-involved-pdfs/partners-in-cancer-diagnosis-newsletter/partners_newsletter_27-july-2018.pdf